Table Of Content

The remains were then escorted across the broad Neva River to the Peter and Paul Fortress, where they will be entombed in today’s ceremonies of repentance and atonement. The cortege of teal hearses slowed as it carried the Romanovs past their imperial home at the Winter Palace, in a symbolic bow to the Russian tradition of returning loved ones after death to their last home. While this adds more melodrama to this particular episode of The Crown, it is likely untrue. Per The Post, Mary and Alexandra did not grow up with each other and were not known to be rivals. But other aspects of the episode are very accurate, such as Queen Elizabeth’s and Prince Philip’s ties to the Romanov family. King George V and Czar Nicholas II were cousins and quite close, so when you hear the Romanovs exclaim that they think it’s “cousin George” coming to save them in Episode 6, it makes sense that the characters made that assumption.

Murder of the Romanov family

Ivan VI was only a one-year-old infant at the time of his succession to the throne, and his parents, Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna and Duke Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick, the ruling regent, were detested for their German counselors and relations. As a consequence, shortly after Empress Anna's death, Elizabeth Petrovna, a legitimized daughter of Peter I, managed to gain the favor of the populace and dethroned Ivan VI in a coup d'état, supported by the Preobrazhensky Regiment and the ambassadors of France and Sweden. The family fortunes soared when Roman's daughter, Anastasia Zakharyina, married Ivan IV ("the Terrible") on 3 (13) February 1547.[1] Since her husband had assumed the title of Tsar of all Russia, which derives from the title "Caesar", on 16 January 1547, she was crowned as the first tsaritsa of Russia.

What Really Happened Between the British Royal Family and the Romanovs?

One question still troubling many Russians, however, is the absence of two victims. No trace of Crown Prince Alexei or Grand Duchess Marie, the second-youngest of the czar’s four daughters, was found in the exhumation. As investigators wound up their probe this month, Russia’s chief forensics specialist, Vitaly Tomilin, dismissed all 10 issues raised by the burial opponents as groundless. Even many local opinion makers beholden to Rossel for their state jobs criticize the governor’s handling of the burial issue as a crude form of blackmail. “This is bread and butter for a lot of people, so some will continue to drag it out,” says Koryakova, now burrowed into academic pursuits unconnected with the Romanovs.

What Happened to the House Where the Romanovs Were Killed?

In time, she married him off to a German princess, Sophia of Anhalt-Zerbst.[1] In 1762, shortly after the death of Empress Elizabeth, Sophia, who had taken the Russian name Catherine upon her marriage, overthrew her unpopular husband, with the aid of her lover, Grigory Orlov. Catherine's son, Paul I, who succeeded his mother in 1796,[1] was particularly proud to be a great-grandson of Peter the Great, although his mother's memoirs arguably insinuate that Paul's natural father was, in fact, her lover Sergei Saltykov, rather than her husband, Peter. Later, Alexander I, responding to the 1820 morganatic marriage of his brother and heir,[1] added the requirement that consorts of all Russian dynasts in the male line had to be of equal birth (i.e., born to a royal or sovereign dynasty). Xenia remained in England, following her mother's return to Denmark, although after their mother's death Olga moved to Canada with her husband,[24] both sisters dying in 1960. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, widow of Nicholas II's uncle, Grand Duke Vladimir, and her children the Grand Dukes Kiril, Boris and Andrei, and Kiril’s wife Victoria Melita and children, also managed to flee Russia. Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, a cousin of Nicholas II, had been exiled to the Caucasus in 1916 for his part in the murder of Grigori Rasputin, and managed to escape Russia.

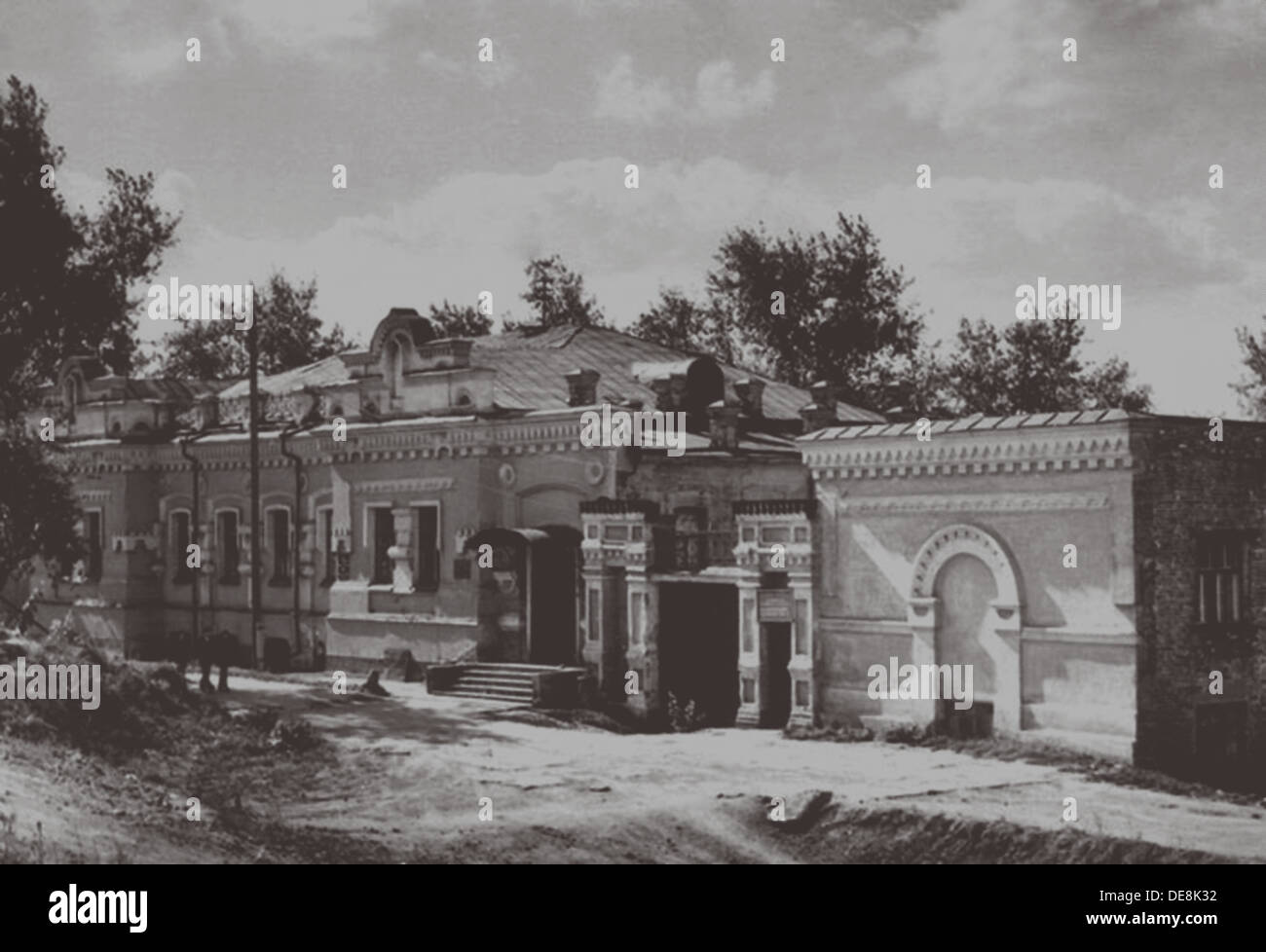

ROMANOV FAMILY: “HOUSE OF SPECIAL PURPOSE” – THE IPATIEV HOUSE IN EKATERINBURG

But protocol argues against interring the servants who died with their masters in the same regal vault with Nicholas and Alexandra. I’d rather they were concerned about paying people who are still alive,” said Pavel, a taxi driver who had been unaware of the ceremonies until police began closing city streets for the cortege. Eleanora Mezeneva, a teacher, called the two-day ritual “the event of the century” and said she approved of the modesty typifying the czar’s last rites.

Murders

They packed their bags and gathered all their things, heading to the basement. The soldiers murdered the family in a brutal, disorganized slaughter that took up to 30 minutes for them all to die. Then, they doused the bodies in sulphuric acid and gasoline before lighting them on fire. Late on the night of 16 July, Nicholas, Alexandra, their five children and four servants were ordered to dress quickly and go down to the cellar of the house in which they were being held. There, the family and servants were arranged in two rows for a photograph they were told was being taken to quell rumors that they had escaped. Suddenly, a dozen armed men burst into the room and gunned down the imperial family in a hail of gunfire.

Contemporary Romanovs

Knatchbull suggests that Mary always worried that Alexandra was prettier and would upstage her. The Crown’s Season 5 episode “Ipatiev House” explores Queen Elizabeth II’s connection to the Russian royal family. Gibbes converted one of the ground floor rooms into a chapel dedicated to St Nicholas the Wonderworker, where the murdered imperial Russian family were mentioned at every service which was celebrated there.

After the February Revolution, Nicholas II and his family were placed under house arrest in the Alexander Palace. While several members of the imperial family managed to stay on good terms with the Provisional Government and were eventually able to leave Russia, Nicholas II and his family were sent into exile in the Siberian town of Tobolsk by Alexander Kerensky in August 1917. In the October Revolution of 1917 the Bolsheviks ousted the Provisional Government. In April 1918, the Romanovs were moved to the Russian town of Yekaterinburg, in the Urals, where they were placed in the Ipatiev House. Here, on the night of 16–17 July 1918, the entire Russian Imperial Romanov family, along with several of their retainers, were executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries, most likely on the orders of Vladimir Lenin. The royal family—and their slimmed down staff—spent 78 days in this fortified mansion turned prison, until that fateful morning of July 17, 1918, when they were woken up at 1 a.m.

The Crown: Fact or Fiction, Episode 20 - Ipatiev House - Daily Mail

The Crown: Fact or Fiction, Episode 20 - Ipatiev House.

Posted: Thu, 18 Apr 2024 07:00:00 GMT [source]

/ Group of Ural Bolsheviks at the Romanovs’ “grave” — the alleged burial place of the Romanovs. More than a century after their tragic demise, the Romanovs and everything about them—from their lost treasures to the enduring mysteries surrounding their deaths—still continue to inspire feverish obsession (for more proof of this see here, here, and here). In the latest season, which premiered on Netflix on November 9, an entire episode is dedicated to exploring the doomed Russian dynasty—and how they were connected to the House of Windsor. Yurovsky spoke briefly to the effect that their Romanov relatives had attempted to save the Imperial family, that this attempt had failed and that the Soviets were now obliged to shoot them all. Yeltsin vowed earlier this week to act on the federal commission’s report within a few days of its presentation next Tuesday and choose among the three proposed funeral sites. Sources close to the president say he favors a St. Petersburg ceremony on the anniversary of the deaths.

That view is shared by geologist Alexander Avdonin, who spent years studying reports from the executioners and the recollections of Ipatiev House neighbors, and located the pit containing the royal remains in 1979. To prevent the site from becoming a magnet for nostalgic monarchists in that intolerant Soviet era, the geologist and his journalist partner, Geli Ryabov, kept their discovery secret for the next decade. Like Rossel and most officials in this city, Nevolin says he hopes Yeltsin will let Yekaterinburg, located about 900 miles east of Moscow in the Ural Mountains, bury the Romanovs in a gesture of atonement for their execution. That designation was long ago made by the Russian Orthodox Church in exile, those faithful who fled the revolution and established an independent religious hierarchy abroad during the 74 years of atheistic Communist rule in the Soviet Union. The question of whether Nicholas should be canonized now confronts religious leaders here with the choice of making the humiliating admission that they were under the Soviet regime’s thumb for those seven decades or remaining at odds with Orthodox brethren abroad. Lyudmilla Koryakova, an archeology professor at Yekaterinburg University who supervised the exhumation in 1991, expresses disgust over the events that have ensued since her team of diggers descended on the grave site along Koptyaki Road north of Yekaterinburg.

He had been receiving angry letters from his subjects, many of whom not only supported the ideals of the Russian Revolution but were opposed to the British monarchy itself. He also became concerned with the realities of having two major imperial families in the United Kingdom. It didn’t help, either, that Alexandra, the tsar’s wife, was German—the very country the United Kingdom was then at war with. “The king has a strong personal friendship for the emperor and would be glad to do anything to help him,” Stanfordham wrote to the British foreign secretary. “But His Majesty cannot help doubting, not only on account of the dangers of the voyage, but on general grounds of expediency, whether it is advisable that the imperial family take up residence in this country.” George asked them to withdraw the offer.

They lived for a time in regal—but closely guarded—comfort in Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. By the summer of 1917 they were moved to Western Siberia, into the safe confines of the Governor's Mansion in Tobolsk. After the Bolsheviks seized power from the provisional government in the fall of that year, things gradually deteriorated for the Romanovs, who were forced to part with longtime servants and give up certain luxuries like butter and coffee. Nicholas and 10 others in the imperial entourage were executed by firing squad in the cellar of a merchant’s house here in the predawn hours of July 17, 1918. The carnage was ordered by Bolshevik revolutionaries who had seized power eight months earlier and who sought to ensure that they would never again be challenged by a monarch.

The 55 volumes of Lenin's Collected Works as well as the memoirs of those who directly took part in the murders were scrupulously censored, emphasizing the roles of Sverdlov and Goloshchyokin. Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?"[92] Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised. The Empress and Grand Duchess Olga, according to a guard's reminiscence, had tried to bless themselves, but failed amid the shooting. Yurovsky reportedly raised his Colt gun at Nicholas's torso and fired; Nicholas fell dead, pierced with at least three bullets in his upper chest.

Yet neither was crowned; Constantine renounced the throne before his brother’s death, and Michael deferred his acceptance of the throne, effectively ending the monarchy. Feodor Nikitich Romanov was descended from the Rurik dynasty through the female line. His mother, Evdokiya Gorbataya-Shuyskaya, was a Rurikid princess from the Shuysky branch, daughter of Alexander Gorbatyi-Shuisky. The corpses were then unceremoniously thrown into a Fiat truck and taken out to the Koptyaki Forest.

For most of his life, Nicholas Romanov kept a diary, writing scrupulously, almost drearily – carefully noting events such as playing cards and having dinner. He did so as heir to the Romanov throne, as Emperor Nicholas II – and didn’t stop after losing his crown in 1917 and becoming just “citizen Romanov”. The centerpiece is the coat of arms of Moscow that contains the iconic Saint George the Dragon-slayer with a blue cape (cloak) attacking golden serpent on red field.

No comments:

Post a Comment